Kalinago residents and officials gather at a traditional meeting house in the village’s 3,000-acre territory on the Caribbean island of Dominica. Photo: UN Foundation/Kreig Harris

First, they overcame colonization. Now, they’re confronting climate change. Meet the Kalinago people of Dominica, the largest remaining Indigenous community in the Caribbean.

As the youngest Chief in the history of the Kalinago people, 26-year-old Lorenzo Sanford understands the weight of the responsibility he carries.

Standing in a meeting house in the Kalinago Barana Auté — a representation of a pre-Columbian Kalinago village — Sanford recalls the moment he decided to run for office. It began, he says, the morning after Hurricane Maria in September 2017. Walking door to door to check on his neighbors, he remembers seeing how the Category 5 storm had ripped the roof from nearly every home he passed.

In 2019, Lorenzo Sanford became the youngest chief in the history of the Kalinago people at the age of 26. He was inspired to run for office after seeing the devastating impact of Hurricane Maria on his community. Photo: UN Foundation/Kreig Harris

The 3,000-acre Kalinago territory runs along the island’s northeast coast, directly facing the Atlantic Ocean and equatorial trade winds. So when Hurricane Maria made landfall, becoming the strongest on record to ever strike Dominica, the Indigenous community was among the first and hardest hit.

Even six years later, the Kalinago territory — indeed, the entire country — is still recovering from its aftermath. Destroyed, yet-to-be-rebuilt homes continue to litter the landscape, along with large swaths of sickly trees stripped bare by Hurricane Maria’s 160 mph winds. It took an entire year for the island to fully regain electricity.

“Dominica is on the frontline,” Donalson Frederick, a member of the Kalinago who manages the territory’s disaster response, told NPR during a UN Foundation press fellowship to the country earlier this year. “Climate change is not something that is happening tomorrow. It’s happening now, and it’s affecting our livelihood now.”

Donalson Frederick, a member of the Kalinago, manages the territory’s disaster response. From superstorms like Hurricane Maria to extreme drought, his community is already grappling with the consequences of a changing climate. Photo: UN Foundation/Kreig Harris

Like so many Indigenous groups across the globe, the Kalinago are confronting the constant threats of a changing climate, from superstorms and ocean acidification to extreme drought and record-breaking heat waves. It’s a truly devastating irony: Our planet’s most effective guardians are being punished by the impact of a small few who are destroying the Earth.

“For thousands of years, Indigenous peoples have pioneered sustainable land management and climate adaptation,” United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres said at the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues earlier this year. “The so-called ‘green economy’ is not a new concept for Indigenous peoples. It is a way of life stretching back millennia. We have so much to learn from their wisdom, knowledge, leadership, experience, and example.”

For his part, Sanford knows that one of his biggest challenges as Chief is preparing his community for the next inevitable disaster. He also recognizes that every Kalinago resident will have to play a role. “Everyone here has a responsibility for things that happen within this space,” he says.

But he also knows this isn’t the first time the Kalinago people have faced an existential threat.

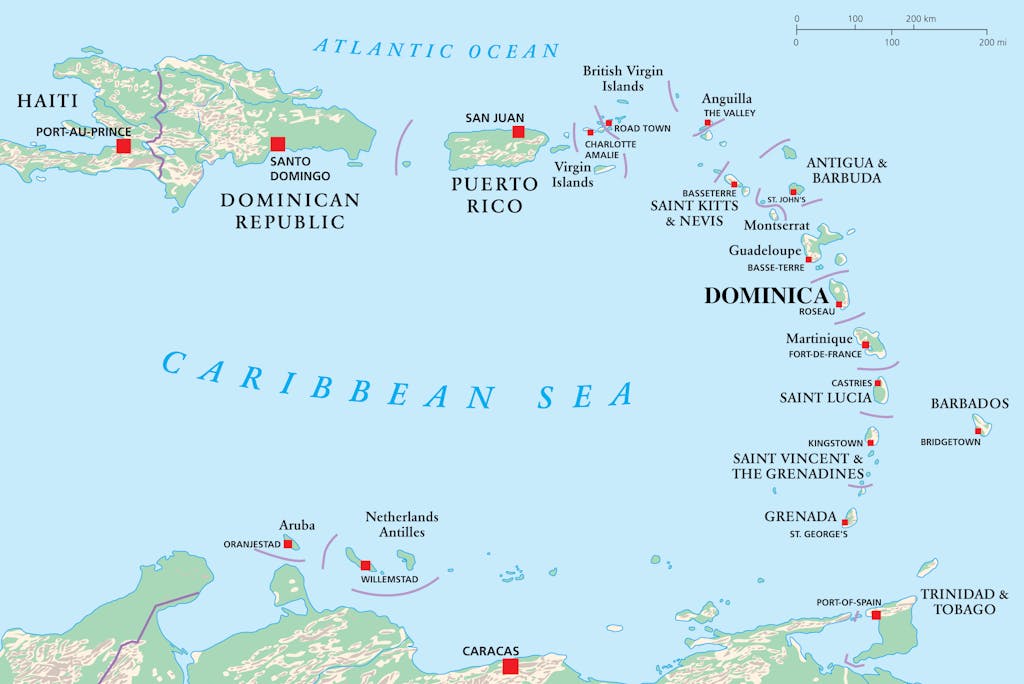

Often confused with the Dominican Republic, the island of Dominica is located in the eastern Caribbean between the islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique. Christopher Columbus landed there on his second voyage to the New World in 1493. Source: Shutterstock/Peter Hermes Furian

A Legacy of Resilience

On his second voyage to the so-called New World in 1493, Christopher Columbus landed on a small island in the Caribbean now known as Dominica. There, he met a local people that called themselves the Kalinago, a word whose meaning has been lost to history; the tribe’s language is considered extinct.

The community itself, however, managed to survive. For the Kalinago, what followed that first contact with Europeans would be nearly 500 years of resistance to colonial subjugation, massacre, enslavement, and eradication. In 1903, they finally gained tribal sovereignty, exactly 75 years before the country of Dominica gained full independence from the UK.

According to Dominican historian and anthropologist Lennox Honychurch, the Kalinago people represent one of the world’s most resilient human legacies, as well as one of its most diverse. In his book, In the Forests of Freedom: The Fighting Maroons of Dominica, Honychurch details how the Kalinago fought colonization while assimilating survivors of shipwrecks, slavery (and sometimes both) to create a multicultural genealogy of African, European, and South American lineages. As a result, both the tribal and national identity of Dominica is one of a “spirit of self-reliance and a respect for the forest citadel of this island that has given its natural resources for our survival and for the continued protection of our people,” he writes in the book’s introduction.

As the island’s original inhabitants, the Kalinago have historically protected its precious biodiversity by honoring the natural cycles of local plants and animals. This means practicing sustainable methods of harvesting and hunting that don’t disrupt growing or reproductive seasons. When extracting seeds from the annatto plant to make traditional dyes for pottery, sun protection, and body paint, for example, the community takes care to avoid depleting too much of the plant.

A connection to the surrounding environment has always been a central element of Kalinago culture. In some villages, locals still use conch shells to warn neighbors across Dominica’s many peaks and valleys about impending storms, floods, or landslides. It’s an ingenious example of an early warning system that utilizes natural resources at hand. Carried by the wind, the primeval sound of this type of seashell can be heard miles away.

An aerial view of the Indigenous territory’s Barana Auté — a pre-Columbian Kalinago village — overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. Photo: UN Foundation/Kreig Harris

Looking to the Past for a Sustainable Future

“Dominica is sort of a petri dish for all island developing states,” says Dominica’s Environment Minister Cozier Frederick, himself a member of the Kalinago. Frederick hopes the rest of the Caribbean can look to his country as a model for sustainable development, including ecotourism.

This means recognizing the tension between expanding the island’s tourism industry and the environmental challenges that come with it. “We are trying to balance keeping nature intact and keeping cultural heritage intact while being mindful that neither may grow if there’s no one outside seeing it, appreciating it, and learning from it,” Frederick said.

Right now the Kalinago are exploring ways to promote and share their unique culture and surroundings while also protecting both from exploitation and extraction. One solution involves an innovative approach to hospitality in which Kalinago residents welcome visitors for overnight stays in the Territory’s homes. The goal is to nurture an intimate and authentic bond with those who visit.

For tribal leaders like Sanford, building a more sustainable future means exploring economic growth beyond tourism. After all, the COVID-19 pandemic revealed the shortfalls of such a singular focus. “The most profitable future for our communities is to develop a diverse set of activities based on farming, tourism, traditional crafts, and community-based natural resource management,” Sanford told the World Bank.

With support from the Dominican Government as well as the UN Development Programme (UNDP), for example, the Kalinago are strengthening sustainable agriculture, reforestation, and infrastructure to help create more jobs on the Territory, as well as conducting workshops about the use of native flora like cassava, calabash, and larouman reeds in traditional crafts, medicine, and cuisine — not only to educate tourists, but also to teach Kalinago youth.

This community-centric strategy reflects a shared reality: None of the tribe’s roughly 2,500 residents own their own land or property; the entire territory is communally owned. Gweneth Frederick, who leads the Kalinago’s Ministry of Tourism, prefers to use the term “regenerative tourism” to describe the community’s philosophy toward economic progress. For Indigenous people, she says commercial development is more than mere consultation with outside groups; it’s about forging equal partnerships and respecting human rights, especially for historically disadvantaged communities like theirs. “It means going back to the elders to find out what they did that kept the forest green, and kept the rivers flowing,” Frederick said. “That is something the Kalinago people have always done.”

Kalinago resident Elizabeth Valmond weaves a traditional basket using locally sourced larouman reeds. The Indigenous territory now operates a small gift shop where they sell their crafts to tourists as a way to generate income. Photo: UN Foundation/Kreig Harris

Leading With Indigenous Wisdom

When it comes to Indigenous rights and representation in Dominica, it seems the tides of history might finally be turning. In a historic presidential election last month, Dominicans elected their first-ever Kalinago head of state, Sylvanie Burton.

Her election also broke another barrier: She’s the country’s first female President — a significant milestone that reflects why representation matters. After being denied their rightful place as local leaders and citizens for nearly half a millennia, the Kalinago now have a voice and advocate in Dominica’s highest office.

For newly elected leaders like Burton and Sanford, it’s their turn to carry forward the Kalinago’s legacy of resilience, sustainability, and survival — hard-won roles that will protect and inspire generations to come.