On October 1, the United States officially changed its visa policy to require diplomatic staff in same sex relationships to show proof of marriage in order for partners to be able to stay in the United States. Without proof of marriage, same sex partners face deportation within 30 days of December 31. This move, which reverses policies in place since 2009, has rightly spiked deep concern about the status, rights, and dignity of LGBTI professionals based in the United States (or soon to be) who work for major international organizations including the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the United Nations.

During a State Department background briefer this week, U.S. officials described the policy shift as the direct result of the 2015 landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision on marriage equality in the United States. The argument goes that this policy change is required in order to harmonize the treatment of international public servants in the United States with the U.S. State Department’s policy on American diplomats and their partners residing overseas. U.S. State Department officials speaking Tuesday, explained the policy as emanating from that 2015 decision and committed the U.S. to “work closely with the UN and the foreign missions to help people meet these new requirements.” This includes an expressed willingness to resolve specific family situations on a case-by-case basis.

But let’s step back from legal and administrative technicalities, important as they may be, to look frankly at the bigger picture.

Same sex marriage is legally recognized in fewer than 30 countries out of 193 that are represented at the UN. LGBTI individuals from any of the 163 countries where there is no marriage equality may face stigma, discrimination, or worse if they are required to take the very visible step of marriage in another jurisdiction just to keep their job or visa status. “Domestic Partner” designation for international professionals has been for many years an essential way to enable same sex partners to have equal rights as professionals, to not expose themselves to added risks or threat in their own countries, and to live and love freely.

In the UN, which has been our professional center of gravity for most of our respective careers, we cannot fathom the implication that LGBTI professionals with whom we have been privileged to serve – including some who have lost their lives in the service of peace and human dignity – would face the stark choice of marriage or deportation simply because they have chosen not to be legally married.

Over 70 countries currently criminalize same-sex relations, let alone marriage. It is no mystery why some couples may opt for “domestic partnerships” over marriage given the risks of attracting stigma, violence, or retaliation. UN-Globe – the organization that supports LGBTI professionals in international civil service – and others are still assessing the number of families that may be affected by the U.S. policy change. Some have estimated it could impact over 100 families that currently reside in the United States; some have estimated fewer. But the larger point is that even one family is too many if their choices are both stark and unnecessary.

While the State Department says the new policy is intended to harmonize policies impacting opposite-sex and same-sex couples, significant questions need to be answered about the potential significant disruption on LGBTI international civil servants and their partners and families.

There is also the question of prospective UN staff members and their partners who, should they reside in one of the overwhelming majority of countries that lack marriage equality, may not be able to keep their family together. LGBTI and ally organizations as well as staff resource groups such as UN Globe should also be carefully consulted.

Above all, families should be supported in staying together. A good faith, and serious, effort by the U.S. Administration is all that is required to observe the Obergefell decision and do the right thing by the families currently and prospectively affected.

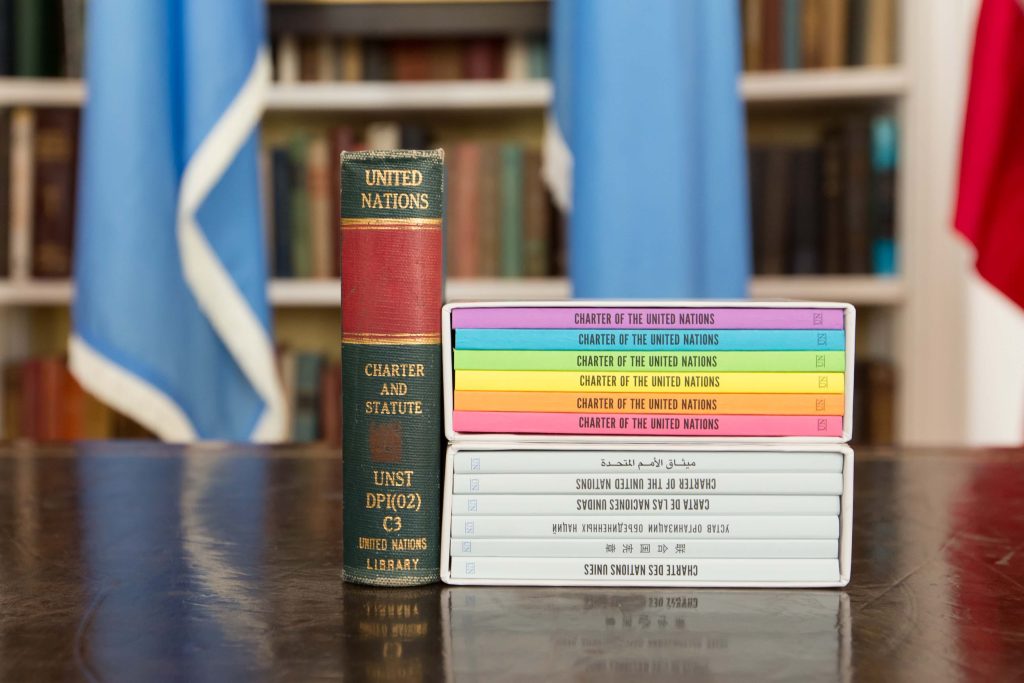

We need look no farther than Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights – shaped so forcefully by American values and the remarkable leadership of Eleanor Roosevelt – which affirms that all human beings are born “free and equal” in dignity and rights.

Who could reasonably argue with that?