“They were warned about the flood, but refused to vacate the area, fearing their sugar cane would be stolen.” – Radio host in Uganda

Those words come from an actual radio broadcast following a flood in the small Ugandan town of Jinja, on the shores of Lake Victoria. More than half of Ugandan households rely on radio as their primary source of information, and as many as 25,000 Ugandans call into local programs on hundreds of radio stations around the country every day. People discuss everything from the light-hearted to the serious, including health care, politics, education, and the effects of natural disasters. Radio communication has been around since the late 1800s, and in many remote and poor parts of the world, it remains a critical communications tool. But now in Uganda, the United Nations is partnering with policymakers, academics, and local staffers to apply cutting-edge artificial intelligence (AI) technology to radio broadcasts to gain greater insight into how to better serve citizens, especially those who might not have access to more modern technology.

“Analyzing radio data can rank critical issues affecting the health sector according to the perspectives of members of the population,” says Dr. Eddie Mukooyo, Chair of the Uganda AIDS Commission Board in the Office of the President. He notes that the policy teams can get “feedback on national campaigns and initiatives like the mosquito net distribution, ambulance services, or contraceptive methods. It’s a way to assess client satisfaction on various health services and projects.”

While UN and government programs gather qualitative data, it is often difficult to collect it from remote areas, especially where local dialects are spoken. Anecdotes and opinions shared on local radio stations can be turned into useful data that can inform development projects and legislation. This information can then be used to develop early warning systems – not just for natural disasters, but also for the spread of diseases, outbreaks of violence, and even corruption.

Turning radio conversations into data

But how can radio conversations be turned into data? Enter Pulse Lab Kampala, the Ugandan branch of UN Global Pulse, that works to leverage big data to improve humanitarian and development action. Pulse Lab Kampala works with partners from different sectors and across UN agencies to support, collaborate, and deliver the best solutions to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

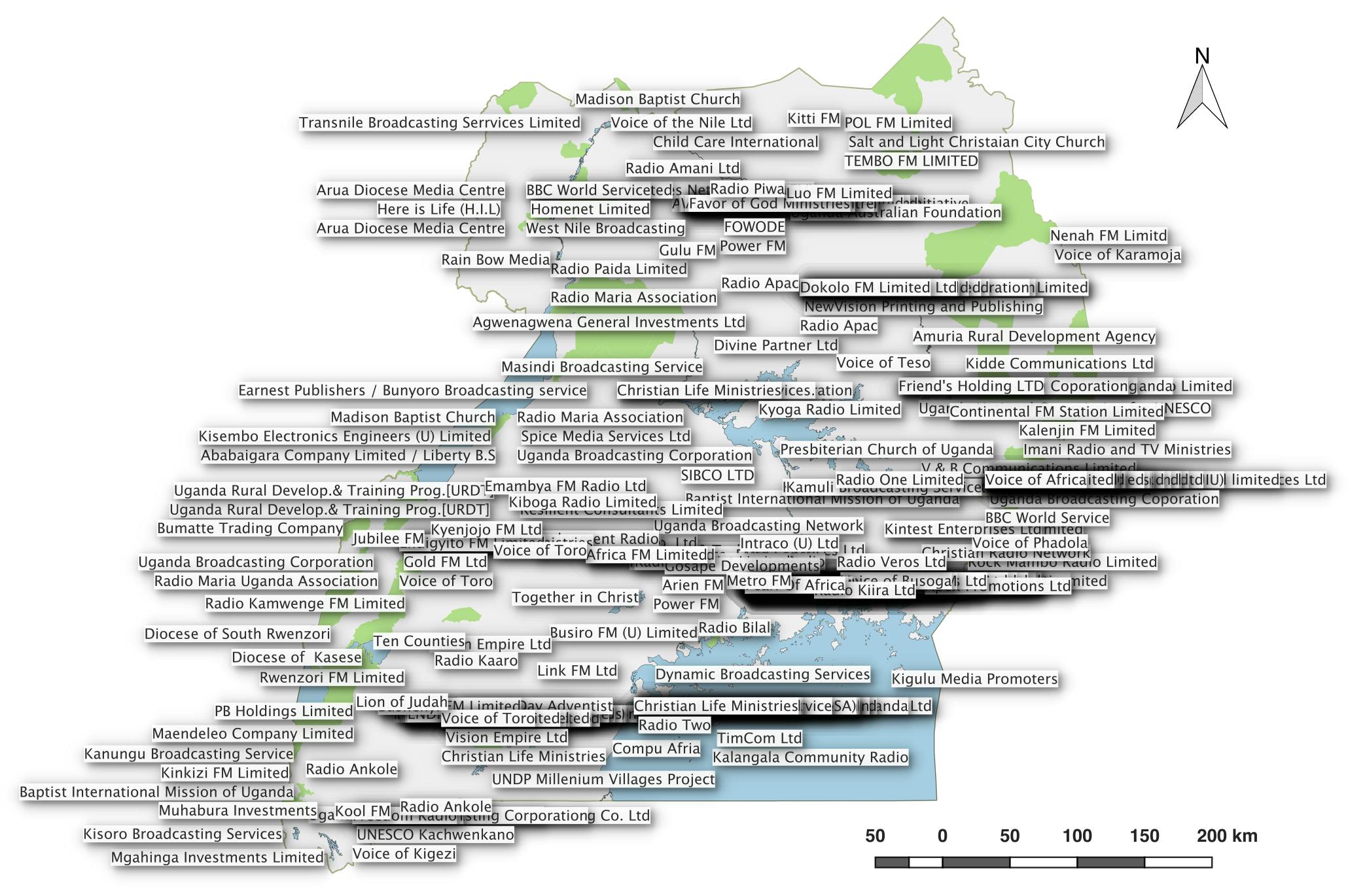

Pulse Lab Kampala’s automated speech recognition tool uses AI technology to pull recordings of radio conversations around set themes, such as health care, refugees, or local disasters and translates the discussions into English. These highlighted clips are then listened to by experts who flag relevant information and enter it into a database. From that database, local governments or the UN can gather insights that help inform lifesaving policy decisions, such as where aid is needed.

By incorporating languages and voices that are not often included in official reporting and analysis, the UN and its partners are working to better understand and target the needs of those for whom progress remains elusive.

To address the crippling information gap from remote and smaller communities, Pulse Lab Kampala worked with Stellenbosch University in South Africa to design an artificial intelligence tool that analyzes data from local public radio stations and delivers key insights to transform policy and accelerate progress on the Sustainable Development Goals.

Bridging the digital divide

“In many places in Africa, including in Uganda, the digital divide is still very much a reality and will remain for some time,” says Paula Hidalgo-Sanchis, manager of Pulse Lab Kampala. “We’ve built a tool that can filter through the content of radio broadcasts, for several languages, to involve more voices of rural citizens in decision-making about where to send aid or how to improve services.”

She continues: “We used convolutional neural networking technology to create Automated Speech Recognition toolkits for local Ugandan languages, starting with the way English is spoken in Uganda, Acholi, and Luganda. We now have a robust set of capabilities that can listen to dozens of radio stations simultaneously, flag relevant content when specific keywords are mentioned, generate a transcript for deeper analysis, and drop the audio segments into a queue for human review.”

Radio callers and broadcasters can provide important insights for local government officials and the UN. Here are some samplings of recording captured from local radio stations that were used for further analysis on issues ranging from health care to girls’ education:

“Eddwaliro lyaffe temuli yadde panadol kyokka nga n’abakyala bazaalira ku sseminti”

Translation from Luganda: After 30 years, they are telling us they have built health centers. The same health centers have no medicine, not even the basic medicine like panadol.”

“Wawinyo ni line mac ongolo wa ki kwene”

Translation from Acholi: Our MP promised us power, but the electricity lines have passed somewhere else. We elected you as our MP to do such a job, so that you bring us power just as other regions are getting.”

“She is supposed to be in class, but they say to her ‘after all, you are a girl. Go and chase birds away from the gardens so that we get a good harvest’, and that girl is just left there.”

Pulse Lab Kampala worked with government and UN partners to identify a series of case studies where this tool was used to raise awareness of key issues. From early indications of rising concern about refugees coming into Uganda from neighboring South Sudan, to insights on the strength of local health care systems, these case studies showed the insights that radio conversations could provide. Local UN offices and government programs were able to integrate these insights to inform their work in Uganda.

For example, Pulse Lab Kampala, in partnership with the UN Development Programme (UNDP) and Uganda’s National Emergency Coordination and Operations Centre (NECOC), examined how radio information could uncover local damage caused by natural disasters. While large-scale destruction is easier to map, small-scale yet life-changing effects – such as the flooding of fields or crop loss – are often not featured in newspapers or through traditional government-reporting mechanisms. By listening to radio stations that cover local conversations, response teams can identify these types of damage faster and respond to them more efficiently.

Using keywords like ‘flood’ and ‘crop’, analysts at Pulse Lab Kampala filtered flagged snippets from public radio stations across Uganda through a two-tiered process: A rapid assessment, which allows them to quickly pull out false matches, and an annotated assessment in which the relevant clips are translated into English and incorporated into a structured, searchable database.

Recordings like the ones below can give officials important insights into issues like local disasters, including where they are happening and how citizens are responding. This helps them to make more informed decisions around policy and interventions.

“People have to migrate.…Their house is full of water and now they have put all of their things, their belongings on top of their heads.…Sometimes you have to stand like that ‘til morning.”

“Wan peko ma tye ka dio wa kany en aye lok kom yo gine road gang en ma o aa ki Palaro odonyo i Paibona. Translation from Acholi: The problem for us is the road going from Palaro to Paibona… the surface has washed away.”

Translation from Acholi: The problem for us is the road going from Palaro to Paibona….The surface has washed away.”

Public data and individual privacy

“Data privacy is a very serious concern even though the data we collect is public,” Hidalgo-Sanchis says. “To conduct analysis, we apply instruments developed by UN Global Pulse in consultation with privacy experts, namely the Data Privacy and Protection Principles and the Risks, Harms, and Benefit Assessment.”

The data privacy and protection principles are applied to all projects conducted by Global Pulse’s three innovation labs. These principles are designed to ensure that every project obtains, retains, and uses data in a way that protects people’s fundamental human rights, including the right to privacy. These guidelines have been replicated by other UN organizations and institutions. These learnings were also incorporated into a system-wide framework of data privacy guidelines adopted by the UN.

Listening, learning, delivering

The tool is not a ‘one-size fits all’ type of solution. One limitation is that every time the lab wants to start analyzing radio in a different language, they have to train a new speech recognition system. And while most case studies proved successful, Pulse Lab Kampala also learned from its failures. For example, one case study sought to analyze anti-malaria tactics, yet it received little information from the Radio Content Analysis Tool. It turns out that the grassroots conversations happening on the radio did not often touch on malaria. Yet this insight still proved useful by showing policymakers in Uganda that public awareness and interest in malaria could be improved.

As with any other type of analysis, mining radio comes with its own biases. For example, in the case studies, analysts found that certain demographics were more likely to be callers. Radio conversations can also be shaped by false information to achieve sensationalist or political objectives. In addition, analysts at the lab found that rural accents were often harder for the AI system to understand than urban accents, which risked skewing the results.

While these challenges must be addressed, the reach of radio means that more voices can feed into local, national, and global policies. By pairing this traditional medium with the latest AI technology, Pulse Lab Kampala is helping the voices of rural Ugandans to be understood, analyzed, and heard. This approach can then be replicated in other countries and settings to provide better support to people who speak in marginalized languages and dialects – helping to ensure no voices are left behind as countries work to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

Want to learn more about how the UN is innovating to improve lives? Sign up to be a champion of innovation.

Innovation in Action shares the stories of how the UN is working with partners to pilot, test, and scale new ideas and new ways of working to deliver better results for people on the ground. From using artificial intelligence to better understand peoples’ needs to innovative methods to reduce maternal and infant mortality to reimagined partnerships and new approaches to mediation, the UN is working across issues and sectors to create dynamic and impactful solutions. The series has been developed with input and support from the UN, including the UN Innovation Network.